-

-

The Discerning Mollusk's Guide to Arts & Ideas

-

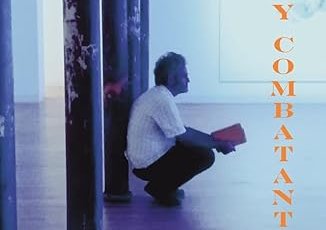

Human Wishes / Enemy Combatant

Edmond Caldwell

Grand Iota, Mar 2022

n 2022 a small UK press performed the small miracle of literary resurrection: they republished a novel whose author had been dead for five years and whose original publisher was also defunct, leaving his novel out of print—the literary equivalent of the Biblical Second Death. Sadly, there wasn’t the same interest in this as there was for that of Lazarus, with no reviews that I can ascertain in America and only one in Britain.

The miracle-working press was Grand Iota, a two-man outfit that punches well above its weight in publishing new fiction and republishing significant out-of-print American novels, including Fanny Howe’s Bronte Wilde and Barbara Guest’s Seeking Air; they have also more recently republished an important collection of essays by Eric Mottram, a pioneer of American Studies in Britain—Blood on the Nash Ambassador.

I had some small involvement in that republication; my account of it is intended as a belated tribute to Edmond—whose non-existence in the world I still haven’t adjusted to.

When my first novel, Vault, was published, Edmond, whom I didn’t know then, saw reference to it somewhere, read it and blogged about it, then sought me out on Facebook. We became friends but also fellow warriors; he told me that what drew him to my novel was its subtitle—an anti-novel; he told me that the chutzpah in that, a sure-fire way to turn readers away, was what had drawn him to it.

I later found out when Edmond’s first novel was published a year later, that his interest stemmed from the fact that that novel too was an anti-novel, more complicated, more ambitious, wittier than mine. I admit that I had initially bought it as a return of favour, but once I started reading it, I was overwhelmed with admiration—and not a little jealousy. I reviewed it three times: on Amazon.com; on the now extinct, I believe, Bicycle Review; then in American Book Review.

We remained friends for some years, although there were hiatuses in that online relationship. Edmond would periodically withdraw from Facebook and our contact became sporadic. So when his final withdrawal dragged on and we lost radio contact, I wasn’t at first concerned—he would turn up again in his own time.

Sadly, he didn’t. It wasn’t until some years later that I learnt of his death in 2017, and then the demise of his publisher and disappearance of his novel.

Having become acquainted with Grand Iota and its list, indeed read several of its titles, I approached them with the idea of reissuing that novel, having by marvellous coincidence obtained the text as a pdf. from another friend of Edmond’s, Steven Augustine—from whose blog I learnt of his death, and who, like me, had loaned out his copy and not had it returned but managed to acquire that pdf.replacement.

To their eternal credit, Ken Edwards and Brian Marley, a.k.a Grand Iota, needed little persuasion, seeing immediately the quality of the novel. They published it with an Afterword by Joe Ramsey; a monochrome version of the original, very witty, back cover alongside it; and a superb new front cover for this edition.

However, in writing this tribute, to both Edmond and Grand Iota, I decided to do some republishing of my own—what follows is the text of one of my original reviews, that which appeared in American Book Review (Vol. 33, no. 5), reproduced with the kind permission of Jeffrey Di Leo.

This was for several reasons: to convey my early response to the novel in its freshness, unclouded by the melancholia arising from the knowledge of Edmond’s death (which makes more poignant the final hopeful paragraph), and to pay tribute also to the small press which first took the risk of publishing Human Wishes/Enemy Combatant—Say It With Stones.

Say It With Stones/Interbirth Books are a small, Dallas-based press publishing mainly poetry; Human Wishes/Enemy Combatant is their first venture into the novel. They are to be commended on their enterprise and audacity no less than Caldwell himself. This is a witty addition to the ranks of the Postmodernist anti-novel.

But “anti-novel” is an over-used and imprecise term. Let’s use the term “novel-in-negative”—less snap but more precision.

Human Wishes proceeds by systematically breaking the rules, confounding the expectations of the novel—plot, character, background setting—so that what we are left with is a novel in reverse.

The rationale for this is given within the text: “If you were to write a truly ‘realistic’ novel it would have to include these histories of lives in labor and labor in lives, each novel would have to be an endless roman fleuve of these loops and strata, each novel a failure because it could not possibly encompass it all, each novel necessarily a fragment and a failure . . .” (p. 129). And to create “rounded” characters depends entirely on such infinitely regressing loops of back-story; on the appearance of psychological depth and temporal depth together causing the effect of realism, because “people just don’t go around doing shit for no reason that’s not realistic, but if they don’t do anything at all it won’t be dramatic, if for example they just wander round in circles trapped inside various non-places such as airport baggage-claim terminals and highway rest stops it wouldn’t be dramatic, you’ve got to be realistic yet dramatic . . .” (p. 159).

So here, in place of plot we have structure, and as reinforcement of the structure, a series of (very funny) running gags. The book is in three parts, each of three chapters. They all function discretely, and are all set in just those “non-places”, “In-Between Places” Caldwell warns against: airport terminal, Parisian hotel complex for “bumped” passengers, the tourist sites of St. Petersburg, rest-stop, shopping mall, art gallery . . .

This last also functions as a brilliant mise en abyme—the gallery is showing an exhibition of Joseph Cornell boxes, those still-lifescapes conjuring a universe in a peep-box. The chapters of Human Wishes work the same way, with a cumulative effect.

It also introduces one of the funniest running gags, featuring a constantly metamorphosing James Wood, the literary critic who is, to my amusement, taken very seriously in America (as he is not in Britain). In fact, the principle of Kafkaesque metamorphosis is at the heart of the book, as themes and settings darken.

For instance, the sixth chapter, “Time And Motion”, is set in a shopping mall bookshop, a B. Dalton bookshop in fact, an extended meditation on Taylorism, the “scientific” basis of industrial (and literary?) production, written in the style of Thomas Bernhard, and every bit as funny and acidulous. It plays with the possibility of Taylor’s book The Principles of Scientific Management turning out to be a parody, an anti-novel in the form of a spoof scientific study. But in passing, it relates Taylorism to the efficiency of the Nazi Holocaust. This is not gratuitous. It links subliminally with a later chapter, a backstory of sorts, although not the realist type Caldwell has dismissed, set in Lydda during the Israeli “cleansing” of 1948.

This in turn, by means of a searing image of a mutely screaming shell-shocked woman, morphs into an elaborate playscript involving Dr. Johnson, his cat, the ubiquitous James Wood, and an early, lost play by Samuel Beckett—Human Wishes. Thus is explained the first part of the title.

The second, Enemy Combatant, is prepared by another running gag—the (anti-)hero’s “facial dismorphia”, his obsessive worry over his appearance. Although of Portuguese-American descent, he is convinced he looks Semitic, either Jewish or, more worryingly, Arabic, equally convinced he will end up being arrested as not just a literary terrorist, intent on “blowing up the novel from within”, but a real, honest-to-goodness, Al Qaeda-type terrorist, an enemy combatant.

This “facial dismorphia” is, then, more than a trope for fluidity of character in place of Realism’s “rounded” character. It is the last and crucial metamorphosis of the book. The final chapter, Enemy Combatant, starts fittingly with a parodic reference to Kafka’s Metamorphosis. And as Kafka’s parables turned to chilling literalism under the Nazis—a whole people turned overnight into “vermin”—so the antihero’s dismorphic worries become real, or apparently so, when he is indeed arrested and interrogated as possible enemy combatant, during which the past scenes of his life/the book return and coalesce into Kafkaesque nightmare; a haunting tour de force to close the book.

It is not, though, despite that nightmare ending, a sombre book; on the contrary, it is bracingly literay in its references, and above all very funny in its wit and linguistic invention. No synopsis could adequately describe it, and this review doesn’t attempt to do so. It attempts only to encourage you to read it, slowly, enjoy the ride, and congratulate yourselves on being among the first to recognize the authority of a writer we will all be hearing much more about in the future.

David Rose, born 1949, resident in Britain, is now retired after a working life in the Post Office. His short stories are published widely in the UK and US, including in The Penguin Book of the Contemporary British Short Story (ed. Philip Hensher, 2018) and partly collected in Interpolated Stories (Confingo, 2022) and Posthumous Stories (Salt, 2013). He is the author of two novels: Vault (Salt, 2011) and Meridian (Unthank Books, 2015).