-

-

The Discerning Mollusk's Guide to Arts & Ideas

-

here are writers we love as readers, for the enjoyment they give us and their angle on the human experience; and there are writers we love as writers, for what they can teach us about our craft. Sometimes a writer is both things to us, but not always. While I enjoy T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, in moderation, for various reasons that don’t bear going into here, they could never serve as models for me to follow, in art or (heaven help me) in life.

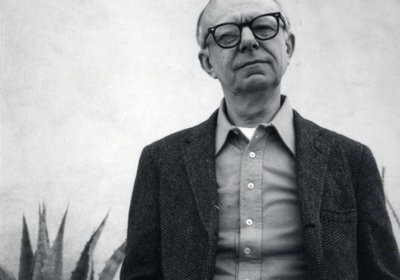

Ever since I first encountered David Ignatow’s poetry in the early Seventies, I have taken much from it as a reader and as a writer. He could be described as the love child of Walt Whitman and William Carlos Williams, with, as Robert Bly observed, a little Hemingway thrown in. His poems are almost always plain and unassuming, usually free verse, occasionally prose poems, yet they pack a powerful sucker punch that sneaks up on you. This is all the more remarkable in that, as James Dickey wrote in an early review, “Ignatow does almost completely without the traditional skills of English versification.” In the right hands, apparently, no technique is also a technique.

The poem I want to discuss here, “For My Daughter,” is quite short, only 15 lines, three simple sentences, two stanzas. It dates from the Sixties and did not find its way into a book until Ignatow’s first collected volume, Poems 1934-1969 (Wesleyan 1970). Judging by how many web sites it appears on today, it must be one of his best-loved works. It begins:

When I die choose a star

and name it after me

that you may know

I have not abandoned

or forgotten you.

Official practice would be to put commas after “die” and “me.” The more sensible practice adopted by Ignatow, regardless of rules, is to avoid punctuation except where the lack of it would leave the passage less clear. Poets should trust their instincts and the intelligence of their readers. His line breaks in this sentence do the work of punctuation, and the run-on first line has the effect of leaping past the idea of his mortality right into how his daughter can begin to handle it. We infer that, just as he is now introducing her to death, he once introduced her to stargazing, an age-old father-daughter pastime. Note how quickly and effortlessly he has made the personal universal. What father has not wondered how to have this conversation with his children? And who else but Ignatow would be so disarmingly direct yet gentle?

The second sentence amplifies and inverts this thought: “You were such a star to me, / following you through birth / and childhood, my hand / in your hand.” Did you catch that? He’s not holding her hand in his, he’s letting her hold his hand in hers, a subtle but meaningful difference, and part of the quiet brilliance of this poem. It is the natural order of things for the caregiver to become the one needing care, and for the child to become the parent. Natural or not, though, it is a painful reality that is difficult to face, and from the beginning he intends to help his daughter do that.

The third and final sentence also functions as the second stanza. It starts by repeating the first two lines of the poem, breaking them a little differently so that the whole stanza has some of the run-on feeling of the first line, for heightened anticipation. By the time we get to the last four lines we are nearly ready for the emotional weight that the poem has accumulated:

…so that I may shine

down on you, until you join

me in darkness and silence

together.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is how you talk to your daughter about death, yours and hers and everyone’s. Small wonder that James Wright titled his essay about Ignatow “A Plain Brave Music” (see Wright’s Collected Prose, The University of Michigan Press 1983).

David Ignatow was born in 1914, the same year as another fine American poet, Randall Jarrell, but outlived his contemporary by 32 years, producing several dozen books of verse. Jarrell died in 1965, and only four years later his Complete Poems was in print. I can hardly believe that Ignatow died in 1997, almost a quarter of a century ago, and we are still waiting for his Complete Poems. I would make a special plea to Wesleyan University Press, which holds the rights to many of his books, and to the Library of America, which specializes in such projects, to put all of Ignatow’s work within easy reach of poetry lovers in his country. It is not too much to ask for this most American of poets.

After years of writing humor for the New Yorker, the Onion and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, among others, Kurt Luchs returned to his first love, poetry, like a wounded animal crawling into its burrow to die. In 2017 Sagging Meniscus Press published his humor collection, It’s Funny Until Someone Loses an Eye (Then It’s Really Funny), which has since become an international non-bestseller. In 2019 his poetry chapbook One of These Things Is Not Like the Other was published by Finishing Line Press, and he won the Atlanta Review International Poetry Contest, proving that dreams can still come true and clerical errors can still happen. His first full-length poetry collection, Falling in the Direction of Up, is out from Sagging Meniscus as of May 2021.