-

-

The Discerning Mollusk's Guide to Arts & Ideas

-

In the words of a woman clearly uneager to be cinematically portrayed, Nelle Harper Lee wrote to poet Ralph Hammond: “There will be no end of hoo-hah with two movies coming out about (Truman). In my old age I must yet again be prepared to duck.”

She’s referring to the films Capote, released in 2005, based on Gerald Clarke’s biography, and, fast on its heels, Infamous, released in 2006 and based on George Plimpton’s oral history, Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career. (Plimpton went to Monroeville to interview Lee for the book but was told she was in Maine, playing golf. He later learned she had been in town but dodged him.)

Capote earned Philip Seymour Hoffman a Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of the writer and a Best Supporting Actress nod for Catherine Keener, who played Harper Lee. The Infamous cast starred Toby Jones as Capote and Sandra Bullock as Lee. Douglas McGrath, Infamous’s screenwriter and director, was wrapping up the editing on his film when Capote, directed by Bennett Miller from a screenplay by Dan Futterman, hit theaters. “We could have rushed to finish and come out at the same time,” McGrath told the Hollywood Reporter, “but nobody seemed to think that was the right idea. Dueling Capotes.”

The two are very different films. Infamous extensively covers Capote’s New York life with the rich society women he dubbed “The Swans” as well as his time in Kansas, researching what would become the “nonfiction novel” In Cold Blood about the Clutter family murders and their murderers. In keeping with the film’s oral history (or “participatory journalism”) source material, there are “testimonials” (as they’re called in the script) by publisher Bennett Cerf, rival Gore Vidal, selective Swans, Harper Lee and others. In these segments, seated before a not very convincing rendition of a glittery New York skyline, characters confide to an unseen interviewer. In an early version of the script, the Capote character also explains himself in testimonial fashion, but someone thought better of the strategy. No Truman testimonials appear in the film.

Infamous, the rangier movie, is longer by some 20 minutes, features multiple flashbacks, favors jump cuts, and covers more of Capote’s life. It also mixes comedy with drama. (McGrath started his career as a Saturday Night Live writer.) The bewilderment of the people in Holcomb when Capote and his trailing scarf blow into town is played for laughs, underscored by a jaunty score. In an overdone joke, the town folk repeatedly call Capote “ma’am.” Unlike Capote, Infamous addresses Capote’s and Lee’s writing struggles following the bestselling success of his In Cold Blood and her To Kill a Mockingbird. Of the two films, Infamous is more sentimental in both its rendering of Capote’s attraction and attachment to murderer Perry Smith and in its presentation of the hardships of the writing life. Bullock is tasked with articulating that difficulty in a testimonial: “I read an interview with Frank Sinatra in which he said about Judy Garland, ‘Every time she sings, she dies a little.’ That’s how much she gave. That’s true for writers, too, who hope to create something lasting. They die a little getting it right.” Other Bullock lines challenging to pull off: “One must remember that at the center of any bright flame is that little touch of blue,” and “I’ve come to feel with great heart-sickness that there were three deaths on the gallows that night.” (The actress is, however, spared a nobody-can-measure-up-to-daddy speech that appeared in an earlier version of the script.)

Miller’s film, Capote, is a moodier, more austere, bleaker and more consistently somber work, set, with few exceptions, where the crime occurred (Winnipeg standing in for Holcomb, Kansas), an isolated place of vast fields and gray skies and unnerving emptiness. In both films, Harper Lee figures prominently, the friend who accompanies Capote into the wilds of Kansas as his research assistant in the winter of 1959. The real Harper Lee was more than eager to go. To Kill a Mockingbird was at long last finished though not yet published. She had time on her hands and an interest in crime in general. Her friend asked for her help, and she gave it. And for her time and trouble, she was paid $900, plus expenses.

On the press junket for Infamous, the ever gracious and collegial Bullock remarked: “Catherine Keener and I were laughing, it’s taken two of us to play Nelle Harper Lee, and we probably still haven’t scratched the surface of who this extraordinary woman is.” Both actresses were asked if they had attempted to meet with Lee prior to filming. “I never met Harper Lee, nor would I ever want to because of the choice she made to live out of the public eye,” Bullock responded. “I have enough respect for her not to have trotted over that line.” Keener had other ideas. Her “first thought,” the actress admitted, was “to march right down to Alabama and knock on her door.” Then she heard the author “wasn’t keen on people making a movie in which she was included” and refrained.

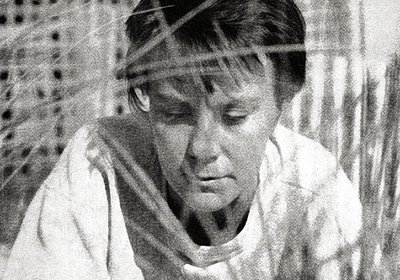

Both Keener and Bullock had the background creds to pull off their believable Southern accents. Bullock, Virginia-born, had the additional advantage of Alabama relatives living in the vicinity of Monroeville. Keener’s father was raised in North Carolina. Keener herself grew up in Florida. Physically, neither actress resembles the sturdier author who, according to Tom Butts, ex-minister and long-time Harper Lee friend, was “not a dainty person.” Although Lee’s “manliness” is referenced in Capote by Capote’s partner Jack Dunphy, nothing about Keener’s person or portrayal of the character substantiates that claim. In reality, Lee was two inches taller than Capote, 5’5’’ to his 5’3”. The Bullock/Toby Jones stats (5’ 7” and 5’ 5”) run closer to the facts. Hoffman was, and Keener is, 5’ 10.” To help carry off the illusion that the actor was a tinier man, the suits and coats Hoffman wore in the film were reshaped and pulled in at the shoulders.

For the most part, Bullock and Keener wear coats, skirts and sweaters in the wintry palettes of black, brown, and dark green, with Keener’s wardrobe being the more tailored and flattering version of the two. Keener’s hair is fashionably waved; Bullock’s short, layered cut with bangs more closely approximates Harper Lee’s true hairstyle. In a bit of business that didn’t make the final cut in Capote, Hoffman “tries to spruce up (Keener’s) limp scarf” while murmuring “Oh, Nelle, you poor thing.” Keener’s Lee needs no sprucing. More effort goes into showing Infamous Lee’s indifference to fashion and preference for comfortable togs. Throughout the film, Bullock wears ankle socks, usually gray. However, in Capote and Lee’s first scene together, the two seated on a New York park bench, Bullock wears white ankle socks with black flats.

Regarding those white socks.

According to The Mockingbird Next Door author Marja Mills (a book reviled by Lee—we’ll get to that), after watching Infamous, Lee wrote to director McGrath “something along the lines of this: ‘You have created a creature of such sweetness and light and called her Harper Lee that I forgive the socks.’” If the “something along the lines of” quote can be trusted, Mills, in reporting it, appears to have taken the comment to be a straightforward, unadulterated joke. No Southerner would miss both its scold and acidic irony. The “sweetness and light” cliché is most often applied to those never-give-offense females who demonstrably lack critical thinking skills. Fair to assume Harper Lee did not consider herself one of that crew.

Although the unfolding investigation of the Clutter murders propels both films, how Lee and Capote work together to find the stories beneath the story is a critical part of the mix. Both films spotlight the closeness of their friendship, the deep knowing that underlies their bond. As observed by Dolores Hope, wife of Clutter family lawyer Clifford Hope, the real Harper Lee “sort of managed Truman, acting as his guardian or mother.” Neither film goes with that interpretation. Both cinematic Harper Lees are in Kansas as helpmates. The difference is in the shading: Keener comes off more partner than secondary. Bullock comes off more self-effacing.

With the exception of a single scene, there is much affectionate indulgence of Capote by Bullock’s Lee, an indulgence that covers his quirks, his misreading of situations, his self-centeredness, his need to shine. When he’s feeling discouraged, she bucks him up. On the street, she takes his arm. When Jones’s Capote embarrasses her—as he often does—Bullock dips her head, glances sideways, faintly smiles. On those occasions when she chides, the chiding is gentle, forgiving. The single break in pattern occurs after a long day in Kansas as the two characters write and type up their findings. The cause of their heated spat is the revelation that Capote now thinks of his book as a “novel” that will apply “fictional techniques to a non-fiction story.” “Reportage means recreating. Not creating,” Bullock’s Lee argues. “The truth is enough.” The squabble ends in a standoff, the scene concludes. Neither the disagreement nor its cause is again mentioned.

Keener plays Lee as a tougher personality, self-contained and self-sufficient, someone who sees more than she discloses, nobody’s fool. Her loyalty to Capote is less absolute, less blind. There is tolerance but no blanket approval. She is there for Truman and will, on occasion, play the noninterfering spectator to his shenanigans, but her character also, with something closer to disapproval than exasperation, notes Capote’s over-the-top manipulative games in Kansas as he woos sources. In large part because of the measured restraint of Keener’s performance, the two scenes in which she lets loose and joyfully cackles (one celebrating the news that Lippincott will publish her novel) are particularly fun to watch. Throughout, her wit is sharp, dry, pointed. “Pathetic,” she tells Capote in their first scene together on the train to Kansas after realizing Capote has paid a porter to flatter him. As they drive toward the Clutter farm past acres of fields, Keener at the wheel asks: “This make you miss Alabama?” “Not even a little bit,” Capote answers. “Lie,” she replies.

Although Keener has fewer lines of dialogue than Bullock, she gets some of the film’s best. (As in Infamous, there are Harper Lee speeches in the script that got axed, including this doozy: “You remember when we were kids? I had no idea what a homosexual was. But I knew whatever they were, you were one of ’em.”) Wise to all her pal’s tricks, Keener’s Lee primarily ribs Capote in private, but in an indication of how comfortable the two have become in the company of lead investigator Alvin Dewey and wife Marie, at a Christmas Eve gathering at the Deweys’ home, a smoking, drinking, laughing Lee mocks, by echoing, Capote’s brag that he has “94% recall” of everything he reads, forcing Capote to laugh too. Even so, she will only put up with so much. At a party celebrating the release of the film To Kill a Mockingbird, after finding a very drunk, self-pitying Truman stashed at the bar, she demands: “And how’d you like the movie, Truman,” walking away when Capote fails to respond. Again and again in Capote, the character of Harper Lee serves as moral conscience and clear-eyed truthteller. After the killers’ execution, when Capote telephones Lee for comfort, she delivers something else: “They’re dead, Truman. You’re alive.” When Capote whines: “There wasn’t anything I could have done to save them,” she refuses to let the self-deception stand: “The fact is, you didn’t want to.” Yet even in lay-it-bare Capote, Lee’s well-known prickliness (her “notoriously peppery persona” in Monroeville native Erin Hall’s phrase) and salty tongue (“the saltiest tongue on earth,” according to friend Claudia Johnson) go missing. Such omissions wouldn’t have occurred by chance. Prickly, salty-tongued sidekicks tend to divert attention from the star.

What neither film omits is the extent and value of Lee’s assistance to Capote in Kansas, further confirmation of which can be found in the 150 pages of typed notes Lee supplied Capote, now held in the Capote archive at the New York Public Library. Divided into ten sections, the notes are organized around the town of Holcomb, the Kansas landscape, the Clutter crime, the four victims, the two Clutter daughters who lived elsewhere, interviews (some of which Lee conducted without Capote), and the trial, in which Lee not only summarized the court testimony but psychologically profiled the jury. Along with objective facts, Lee interspersed opinions, impressions and judgments. Lead investigator Dewey rates a “handsome.” Prosecutor Duane West is considered “a slob.” The “Christian books and magazines” alongside Herb Clutter’s easy chair amount to “modern religious crap.” Bonnie Clutter was “probably one of the world’s most wretched women . . . stomped into the ground by her husband’s . . .efforts to regulate her existence.” Daughter Nancy’s “family life was ghastly.” Killer Perry Smith resembled “a small deacon . . .prim.” His partner-in-crime Richard Hickock confounded Lee by appearing “so poised, relaxed, free & easy in the face of four first degree murder charges.”

In Cold Blood, published in 1965, was “never meant to be a joint project,” Lee told Claudia Johnson. Nevertheless, Johnson and others close to the author subsequently reported Lee felt hurt and betrayed when Capote’s only acknowledgment of her contributions came in the form of a dedication shared with Jack Dunphy. Asked by Capote to do so, Lee had read the manuscript pre-publication. “She was written out of that book at the last minute,” Johnson maintains. Lee’s objections to Capote’s blending of fact and fiction, as dramatized in the Infamous scene between Bullock and Jones, were not immediately known to the outside world. In public, for many years, she remained a staunch supporter of both the book and Capote. Only later, as their friendship frayed—and with greater frequency following Capote’s death—did she give vent to long-held grievances against her onetime friend, calling Capote a liar and, as reported by Marja Mills, a “psychopath.”

Why did the friendship fray?

In the PBS American Masters documentary about her sister, Alice Lee explained: “It was not Nelle Harper dropping him, it was Truman going away from her.”

Lee herself gave different explanations to different people.

To Claudia Johnson, Lee denied that the friendship had turned “sour” because Capote “did not acknowledge her contributions to the book.” It soured because “for the last twelve or fifteen years of his life,” Capote “seemed hell-bent on destroying everyone who had ever loved him.”

To Donald Windham and Sandy Campbell: “Truman did not cut me out of his life until after In Cold Blood was published . . . Our friendship . . . had been life-long, and I had assumed that the ties that bound us were unbreakable.”

To Wayne Flynt: “I was his oldest friend, and I did something Truman could not forgive: I wrote a novel that sold. He nursed his envy for more than 20 years.”

The two authors did not mend fences before Capote’s death in 1984. Yet Lee made the cross-country trip to attend Capote’s memorial service in Los Angeles. Among the others paying their last respects, Alvin and Marie Dewey of Garden City, Kansas.

To Kill a Mockingbird’s immediate and tremendous success profoundly shocked its author. “It was (like) being hit over the head and knocked cold,” Lee told Roy Newquist of New York’s WQXR in one of her last interviews. Published in 1960, the book’s initial popularity was many times compounded and extended by the success of the movie adaptation, starring Gregory Peck, released in 1962. “My baby sister that we thought would have to be supported all her life could buy and sell us all at the drop of a hat,” Harper Lee’s other sister Louise (“Weezie”) wrote in amazement to a family friend. When, in 2009, Lee filed a lawsuit against her former agent, her book royalties, as reported in court documents, exceeded $9,000 a day.

In the early going of Lee’s altered existence, she was still able to write humorously to friends about her status change. To John Darden, two months after the publication of To Kill a Mockingbird, Lee wrote: “I have been to the four corners of the United States and back: In Kansas, where Truman Capote & I spent a bleak winter solving 4 murders for the New Yorker; . . . in New York, where I became Famous; in Connecticut, where the Famous go to get used to it; in Easthampton, where the Famous go after they’ve gotten used to it” and more in that vein. In such communiqués, she gives the impression of being overscheduled and lingeringly bewildered, but the crankiness and bitter resentment from continuous intrusions into her private domain have yet to set in. For four years, she dutifully made the rounds, promoting both book and movie, and then she was done. As sister Alice explained in the PBS documentary: “As time went on, she said that reporters began to take too many liberties with what she said. She just wanted out . . . she felt like she’d given enough.”

In 1947, following the success of The Glass Menagerie and four days before the even bigger hit A Streetcar Named Desire opened on Broadway, Tennessee Williams published an essay titled “The Catastrophe of Success.” In it he mournfully admits: “You cannot arbitrarily say to yourself, I will now continue my life as it was before this thing, Success, happened to me.”

Harper Lee, it can be argued, gave it her best shot.

When Lee settled in to watch a “bootlegged copy” of Capote, sent from Los Angeles by Gregory Peck’s widow, Veronique, Truman Capote had been dead for more than 20 years. Lee herself was experiencing age-related difficulties, including pronounced hearing loss. At age 79, she was watching Hollywood’s rendition of her 33-year-old self.

Working the remote was Marja Mills, a former Chicago Tribune reporter who had moved into a rental next door to the Lee sisters on West Avenue in Monroeville. Because Lee had trouble hearing the dialogue, Mills frequently stopped the tape to repeat the actors’ lines. From this on-the-spot witness, we learn that Lee declared the movie Clutter house “nothing like” the actuality, which was “sort of modern.” (Stock photos of the Clutter house show a yellow brick ranch with multiple picture windows.) Lee laughed loudly at the idea of a movie premiere party, wondered “why filmmakers make so much up in movies about real people,” thought Hoffman’s portrayal of Capote “uncanny” and predicted his Oscar win.

But what, what, what did she think of Keener’s portrayal of herself?

If journalist Mills inquired (and how astonishing if she did not inquire), Lee’s response is not recorded in The Mockingbird Next Door.

Among the tidbits Mills did see fit to include in her memoir/biography are descriptions of the “musty,” cluttered, book-piled, unairconditioned, outdated house the author, when not in New York, shared with her older, lawyer sister Alice, the “baby” sister occupying what had been their father’s larger bedroom. The world-famous writer, we’re told, still typed on a manual typewriter, loved catfish, potato “logs,” McDonald’s coffee, golf, small-stakes gambling, college football and feeding ducks; had a habit of stabbing the air with her index finger to make a point; had a “temper”; and “when something set her off could get creative with her cursing.” If she’d had too much to drink, she dialed up acquaintances and “chewed” them out. She got her hair cut in the kitchen of a retired beautician. She bought clothes at the local Walmart and washed those clothes at a laundromat in Excel, one town over from Monroeville.

In Mills’s explanation, the Lee sisters’ “decision to let me into their lives as fully as they did had not stemmed from one grand declaration but, rather, was a gradual process.”

In 2011, having gotten wind of Mills’s plan to publish a book, Harper Lee issued a statement through her attorney refuting her cooperation in any such project and unambiguously denying that she had “willingly participated in any book written or to be written by Marja Mills” or “authorized such a book.”

Following The Mockingbird Next Door’s 2014 publication, Lee again released a statement to the press: “Miss Mills befriended my elderly sister, Alice. It did not take long to discover Marja’s true mission: another book about Harper Lee. I was hurt, angry and saddened, but not surprised . . . Rest assured, as long as I am alive any book purporting to be with my cooperation is a falsehood.”

Marja Mills’s literary agent countered that Mills had “the written support of Alice Lee . . . and prior to Harper Lee’s stroke in 2007 she had the verbal support of Harper Lee.”

On a break from her life and career in Chicago, a young journalist moves next door to two elderly sisters in a small Southern town.

Sounds like a horror flick pitch, does it not?

Kat Meads's essays have appeared in Full Stop, New England Review, AGNI online and elsewhere. Her most recent book is These Particular Women (Sagging Meniscus, 2023).