-

-

The Discerning Mollusk's Guide to Arts & Ideas

-

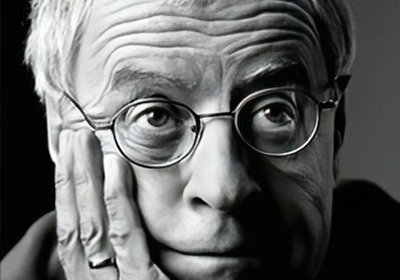

We often hear someone described as “a citizen of the world,” a silly, empty phrase that usually seems to refer to a person who can afford to jet all over the place without any particular purpose. But in the case of Charles Simic it is the literal truth. Born in Belgrade, Yugoslavia in 1938, he and his Serbian family were among the millions displaced by World War II. They suffered hunger, physical danger, oppression, and the no less severe psychic oppression of being without a real home for years on end. This traumatic formative experience must surely be at the heart of the sense of strangeness and permanent dislocation so central to his poetry.

By 1954 their situation had become dire enough that they immigrated to the United States when Charles was sixteen (his father had come over first, followed by Charles, his mother and his brother). After a year in New York City they relocated to Oak Park, Illinois. He finished high school there and several years later was drafted into the U.S. Army, ironically becoming one of the soldiers who had made his early life so miserable and unsettled. Afterwards he was drawn back to New York and graduated from NYU in 1966.

He had already been writing poems for years, quite excellent poems that were not in the least tentative or immature. He had been forced to grow up quickly, almost at gunpoint. Perhaps because of this he appeared to arrive on the American literary scene fully formed. You could say that his further development as a poet did not involve any significant changes in outlook or approach, only a never-ending quest for greater concision and evocativeness. Has any other writer done so well with English as a second language except for Vladimir Nabokov? I don’t think so.

Although Simic’s first full-length collection Dismantling the Silence would not arrive until 1971, he had already published two chapbooks with Kayak, at the time one of the half-dozen most important literary magazines and small presses in the country. His first chapbook, What the Grass Says (1967), is as good as anything he ever wrote. With another writer this might be a way of saying that his later work failed to live up to the early promise. With Simic it is simply an acknowledgment of how great he was right from the beginning. According to AbeBooks, a copy of this rare treasure will cost you anywhere from $75 to $505, and let me tell you, it’s worth every penny.

The title of What the Grass Says comes from a line in the poem we’ll be looking at here, called “Evening.” This free verse poem is outwardly simple and direct, like most Simic poems. In this original form it consists of three stanzas, the first containing four lines, the second containing seven lines, and the third containing five lines. Later, as we shall see, he cut the last line before including the poem in Dismantling the Silence. Here’s the first stanza:

The snail gives off stillness.

The weed is blessed.

At the end of a long day

The man finds joy, the water peace.

There’s a lot to unpack here, even at this early stage. The first two sentences are so short that, at two lines, the third sentence almost feels like an epic. It would be easy to say, wait a minute, Mr. Poet, and start questioning things. Isn’t the snail always giving off stillness? In what sense can a weed be described as “blessed”? To do so, however, would be unseemly and also beside the point. He’s clearly setting the scene here and establishing the mood.

Yes, the snail is always giving off stillness. The little hermaphrodites can sleep for up to three days. But maybe the poet didn’t notice the stillness until evening came. The weed could be called blessed in several ways. First of all, for surviving another day without being mowed down (could this also be one reason the man “finds joy”?). And secondly, for merely being part of the idyllic tableau despite its lowly status as an unwanted plant (again, I feel there is an intentional if unstated parallel to the human). Joy can be found in many ways. There is the honest joy of work completed, implied by the “long day.” And also the joy of setting aside mundane concerns to enter into the spirit of a special moment at day’s end, like the water that has found “peace,” presumably because the wind has died down and it is no longer rippling.

The second stanza starts by seeming to reinforce the quiet pastoral feelings of the first stanza. It calls for everything to be “simple” and “still.” But then it also calls for everything to be “Without a final direction.” Why the sudden note of uncertainty? Well, things are about to get darker rather quickly:

That which brings you into the world

To take you away at death

Is one and the same;

The shadow long and pointy

Is its church.

What else does evening bring besides stillness and peace? Lengthening shadows. And these inevitably turn the mind toward the great mysteries of life and death and whether there is anyone or anything behind it all. In other words, the meaning of it all. Only the poem is much more nimble than my prose. It doesn’t present the shadow as an overt symbol of anything but rather as a thing-in-itself that happens to embody these resonances. Because that’s what humans are, that’s what we do. We aren’t snails or weeds or even water (at least, not more than sixty percent).

The third and final stanza offers yet another turn that, to my mind, synthesizes the feelings of the first two stanzas. It integrates the quiet stillness with the shadow:

At night some understand what the grass says.

The grass knows a word or two.

It is not much. It repeats the same word

Again and again, but not too loudly . . .

The grass is certain of tomorrow.

The idea that nature continually speaks to us is something that science, indigenous cultures and ancient wisdom have in common, though from very different viewpoints. The image of the grass having a simple call, like a bird, is straightforward, charming and distinctly inventive. Which is to say, typical Simic.

It does raise a question, however. In the first stanza the overall stillness and the peace that the water finds suggest that the wind is not blowing. The breeze, if there was any during the day, has subsided. So, is what the grass says a sound, like the sound the wind makes blowing through a field? Or is it another silence? It could be either. Or both. Sometimes the wind picks up again in the evening as a result of the temperature change. Sorry, I’m not purposefully trying to be too literal here. That’s not the best way to approach any poetry, especially Simic’s. I simply wish to understand how he created this wonderful poem and how it works its magic on us. Contemplating this poem makes me think of that marvelous Robert Frost couplet, “The Secret Sits”: “We dance round in a ring and suppose, / But the Secret sits in the middle and knows.”

I’m all right with letting questions remain questions and ambiguities remain ambiguities. One thing I do know is that the original last line is a clunker, an awkward bit of tacked-on anthropomorphism that adds nothing and subtracts a good deal of the mystery. I can hardly believe the line made it into the chapbook that took its title from the poem. Simic was dead right to cut the line when the poem was reprinted in Dismantling the Silence.

The business of revising one’s work after it has already been published in a book can nonetheless be tricky, as another example from Simic shows. I’m talking about the title poem from Dismantling the Silence, which first appeared in his second Kayak chapbook Somewhere Among Us a Stone Is Taking Notes (1969). When he put it into his first full-length collection it was unchanged. By the time of Selected Early Poems (1999) he had lost faith in the ending and tried to fix it. As of course it was absolutely his right to do. Yet in my humble opinion he mucked it up horribly. Thanks to the internet and Kindle and used bookstores we will always have the first version to look at so we can make up our minds. At the end of a long day, that is what brings this man joy.

After years of writing humor for the New Yorker, the Onion and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, among others, Kurt Luchs returned to his first love, poetry, like a wounded animal crawling into its burrow to die. In 2017 Sagging Meniscus Press published his humor collection, It’s Funny Until Someone Loses an Eye (Then It’s Really Funny), which has since become an international non-bestseller. In 2019 his poetry chapbook One of These Things Is Not Like the Other was published by Finishing Line Press, and he won the Atlanta Review International Poetry Contest, proving that dreams can still come true and clerical errors can still happen. His first full-length poetry collection, Falling in the Direction of Up, is out from Sagging Meniscus as of May 2021.