-

-

The Discerning Mollusk's Guide to Arts & Ideas

-

To Henry Bauër

She followed me like an obsession.

Hers was a woman’s face which, it’s true, gave an impression of muteness. She had a straight nose, hard blue eyes, and beneath her blond hair which was pulled back in two small pigtails that started near her temples, she had a rather prominent forehead that was lined with obstinacy. Her hair, bright, soft and yellow crowned her like a helmet, and fell to the nape of her neck so that it looked like a metal collar. But on that stubbornly mute face, the greatest attraction was, like a true mystery, the smile; a scarlet smile with full and sinuous lips, as if sealed by some unbreakable promise the imperious smile of a soul that denies itself, a smile that did not smile.

Modelled in wax, the head was intricately delicate in tone and detail, and in the dim light of the studio, which I had just followed Gormas into, that head, motionless on its base, almost supernatural in the intensity of its proud mouth and lapis eyes, said no. Was it the twilight? In the ambiguous surroundings of the studio that was cluttered with all manner of objects, old clothes, and the white nakedness of statues vaguely animated by the night, an imperceptible frown, doubtless due to some play of light, seemed to accentuate its indomitable expression of defiance.

“Symphonica eroïca; the heroic symphony,” Gormas whispered in my ear as I approached the base, trying to decipher the strange words that were written on it.

“Yes, it is, quite simply, equal to Beethoven’s heroic symphony, but the curious thing is that the woman depicted on that head with its unwilling smile, its predatory profile, actually exists. From morning to evening, she walks through the streets of Auteuil and you can meet her there every day.”

“A model?” I ventured, intrigued.

“No, not at all. She agreed to climb onto the model table for one time only, and persuading her wasn’t without difficulty. She didn’t want to become a goddess, but I begged her until she agreed. And you have to admit, it would have been a great shame if such a woman hadn’t agreed to let such a vision be evoked.”

With his hands behind his back, Gormas, like me, stared in admiration at the painted wax eyes that appeared to have become dreamily distant.

“Yes, she reconciles one with life,” he said, continuing his train of thought, “and she almost consoles one for the boredom of walking there. One can see such creatures there, and even then does one really see them? No, because if you passed Rayon-d’Aube (that’s what I call her) in the street, you wouldn’t recognize her. The best proof is that you’ve already seen her a hundred times and she hasn’t made the slightest impression on you. A pretty woman passing by is either a possible or sometimes an impossible night, if one is prepared to spend five or twenty louis, give or take. After all, what one desires at twenty is different to what one desires at our age. Sadly, one looks at a young woman with a sigh of regret and lets her go elsewhere. One grows so weary, so far removed from others and from oneself that one’s heart becomes afraid. What’s the point of trying again? There is nothing true about women except for the idea we have of them. We sing romantic songs to dolls and as soon as the singer has something in his belly, the doll becomes a statue. Look at this wax head, Rayon-d’Aube is a beautiful, pale, blonde woman that Paris has kept hidden. Ringel met her and drew from her this mysterious face of heroism and refusal.”

“So it’s Ringel we have to thank,” I said. And then I asked: “Who is Ringel?”

“Ringel,” Gormas replied, “is a very curious, little-known artist that I think will interest you. I’ll introduce you… He lives just a stone’s throw from here, on Avenue du Point-du-Jour. Meet me here tomorrow morning and I’ll take you to his studio, but let me give him notice. He’s very touchy, very eccentric, and a bit wild. He confines himself to the gatehouse of the Champ de Mars, as well as the Champs-Élysées, for after having been presented with the Medal of Honour there, he believes himself to be persecuted, the victim of a cabal or at least of an injustice, and doesn’t willingly let anyone enter his studio unless they’re invited. He’s quite violent, has the temperament of an adventurer, and the physique of a Renaissance military leader, he will no doubt be of great interest to you. But it is getting dark, so let me light a few lamps.”

“There’s no need,” I told him. “I have to be going.”

And having announced my departure, I left.

We went through a wrought iron gate into a small courtyard. On the other side of the courtyard was a shed with a glass roof. There was a ring attached to a rope that when pulled set a rusty bell ringing. After a while, a tall, slim, muscular man in a tight-fitting blue sweater half-opened the shed door.

“Come in!” he shouted.

It was Ringel.

I sat in his studio, which was cluttered with monumental chalky white statues, and placed on shelves here and there were the disturbing and frozen smiles of painted wax heads, and I watched that graceful, tall, blonde man with a tanned complexion, as if he had been browned and then reheated, as he bustled around a large piece of wet clay that he was sketching, with the agility of a clown and the attentive suppleness of a watchful cat, I couldn’t help but go through my memory for all of the absurd and crazy stories that I had been told about this Ringel.

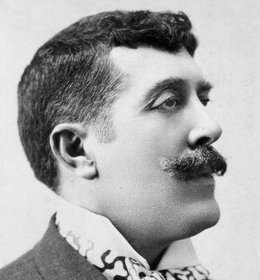

His expressive and tenacious head, his sardonic, sensual mouth and even the colour of his warm complexion that was darker than the pale blond of his moustache, were certainly the features of a man of adventure and audacity, and he looked like one of those brave half Lorraine, half German companions that the Duke of Guise had brought to the Court of the Valois and which one is always surprised to find, in the chronicles of the era, nonchalantly leaning, a dagger in one hand, a cup and ball in the other, under the fleur-de-lis coffered ceilings of the Louvre, with a smile sharpened by the corruption of the times, one of those dangerous and sophisticated men who became Italians during the Florentine intrigues of Henri III and Catherine.

Almost opposite me was a plaster cast of a large naked woman with an ambiguous smile. She was leaning, or rather half-leaning, towards a small mirror she held in her hand. Her wavy hair, decorated with threads of pearls, was certainly that of a Madame de Sauve or one of those perverted and perverting maids of honour employed by Madame Catherine to dissipate the energy and lessen the determination of the partisans of the Béarnais or the Lorrain, the enemies of the king. If the theory of avatars is true, it was in some corridor hung with tapestries in the castles of Blois or Amboise that Ringel must have once encountered this insidious and smiling creature. She smelled of traps, ambush and lust, and on the night of Saint Bartholomew’s Day she must certainly have, like many women of that time, passionately embraced the murderer of the day in the bed still warm from the previous day’s activities, very happy to find the taste of the blood of the murdered on the lips of the chosen lover of the moment.

Perversity was the statue’s title, and I remembered the scandal it had caused in 1878 at the Salon, and the uproar and outrage that had been stirred up by the warm transparency of its flesh, the polish of its thighs and the pink moisture of its lips; for the figure was entirely made of wax, and it palpitated in its equivocal and delightful pose with such life that it was able to emanate danger and exasperate desire. The public reacted to it as if it had committed an act of indecency, so much so that certain people in high places became very upset, and orders were given to remove the scandalous statue.

Obviously the artist objected to this. On having his objection dismissed by the court, he refused to recognise the judiciary’s right to suppress his work and, with the violent determination of a man from another era, he had stood guard for two nights, revolver in hand, in front of his wax figure. And just like a heroic knight who would stand guard outside his lady’s chambers, ready to resort to any means to protect her, when the commissioners that had been sent by the authorities came to remove the statue, the sculptor bravely engaged in the struggle at the feet of his Perversity, which, after being rocked and pulled from all sides, broke into pieces and collapsed onto its base, a strange symbol of a work not wanting to survive the affront inflicted on its creator.

That Benvenuto Cellini-style adventurer was indeed very much like the man himself, and the more I looked at him with his bold profile, his closely shaved head, and his muscular shoulders beneath the heavy cut of his fleece, the more easily I pictured him standing proudly in front of his statue, arms crossed over his chest, standing up to the crowd and challenging anyone to touch his work. And why had his Perversity suddenly collapsed? Was it pure chance; was there not something of the sorcerer about the man?

He had returned from Florence or at least from the court of Valois where in between his time with Madame Catherine and René the Florentine, he had lived in a society that was entirely devoted to the science of potions and bewitchments. Consequently, he must have brought back some mysterious secrets of the occult and the alchemist’s art; for amongst the plaster busts and clay masks there were, peculiarly, the two wax heads upon which my gaze now lingered: two heads modelled in the Florentine style with thick hair that haloed the forehead like a nimbus, both clearly figures of the Renaissance.

One of the heads was of a boy aged somewhere between twenty and twenty-five years, with a sharp profile, thick, beardless lips, a jutting jaw, and with the thumbprint of the sculptor on his chin. It vaguely recalled the portraits of Lorenzo de Medici that were on display in galleries and museums. The cavalry officer’s gorge, the curve of the cuirass, and the steel plates of the helmet covering brown curly hair completed the arrangement; it was a vigorous and bold work.

The other, on the contrary, was the head of a woman or a young, effeminate boy with pale, pink lips which pouted stubbornly. The pale translucence of his slightly feverish flesh and the look of terror of his eyes was evidence that he had lived and experienced intense suffering, and I do not know what cruel memories emanated from that terrified and mute young head.

The painful, ardent and sickly head

Has in the sombre charms of its native grace

The attractions of a virgin and a perverse boy.

Favourite of a bishop or learned Ophelia,

His enigma is suffering, intoxication, madness

Which like a black potion flows into his green eyes.

Certainly, those bruised eyes and that pallor spoke volumes in their silence; she had suffered in her flesh and in her soul. Into what horrible pleasures had she been initiated? But, as I looked into that child’s eyes, eyes which had become the eyes of a woman by dint of staring at some atrocious nightmare, an inexplicable sense of pity seized me, heightened by unhealthy curiosity.

It was in the castle of Tiffauges, the lair of Gilles de Rais, that I first encountered the sinister truth regarding that terror-stricken head, and then, inevitably, several mysterious stories came back to me about the candle makers of the Middle Ages and the public disapproval attached to certain aspects of their trade. I heard that they lived in cellars, in an eternal chiaroscuro conducive to magic and apparitions Their visionary art (with which they invoked the real image of life) was closely related to that of sorcery: rituals and rites were carried out using wax figures. Witchcraft trials are full of references to them being used, and there was one legend that haunted me above all, that of the Anspach sculptor who slowly extracted the soul and life from his model to animate his painted wax and, once his masterpiece was completed, waited for nightfall to go and bury the corpse in one of the ditches of the earthworks.

Had Ringel guessed my thoughts?

“That pretty head, eh?” he said, pointing to the waxwork that looked as if it had been kneaded from pure terror. “It was a little Italian who asked me do it, and although today’s artists claim there are no more models, it’s simply because they don’t know how to see. I met that one in the street one December evening, shivering, gaunt, and almost begging. He took me for an assassin and he was afraid . . . it was his terror that I caught; he was deliciously frightened.”

“And what happened to him?” I asked, a little troubled.

“Huh! The same thing that happens to them all when they pose too young and, as children, live in poverty in Paris. I think he died of consumption.”

“Are you certain?” I insisted.

“Oh yes, he really is dead. Isn’t he, Gormas? Little Antonio Monforti in Beaujon?”

And as Gormas nodded yes, I heard a voice whispering in my ear:

“That is the sort of wax that you need.”

R.J. Dent is a poet, novelist, essayist and translator. He has written three novels, a book-length study of Emily Dickinson’s poetry and a true crime book about Blanche Monnier. He has also translated several European classics into English, including works by Baudelaire, Sade, Lautréamont, Jarry, Breton, Louӱs, Artaud, Crevel and Ėluard. His website is www.rjdent.com.

Jean Lorrain, (1855–1906), born Paul Alexandre Martin Duval, was a French poet and novelist.