-

-

The Discerning Mollusk's Guide to Arts & Ideas

-

wenty years before his first gubernatorial triumph, George Corley Wallace Jr. of Clio, Alabama, campaigned for the favor and affections of Lurleen Brigham Burns of Tuscaloosa, achieved his objective, proposed marriage and was accepted. He was 23; she was a just-graduated-from-high-school 16. The couple had met at a Kresge’s dime store, where Lurleen worked the cosmetics counter. “He had the prettiest dark eyes, and the way he’d cut up!” a smitten Lurleen recalled. She was a Southern gal who preferred the outdoors and being in it, hunting, fishing, swimming. In appearance, she was “small and rather mousy . . . not an easy woman to spot in a crowd,” according to journalist Shana Alexander. In a backhanded, narrow-field compliment, Wallace biographer Marshall Frady deemed her “attractive in that hard, plain, small-faced, somewhat masculine way that Deep Southern women tend to be attractive.” She had zero interest in politics. But when her power-hungry spouse, unable to succeed himself as governor, had the bright idea of running her as his shadow puppet in 1966, Lurleen obliged, won the election and died in office, age 41, from cancer.

Restored as Alabama’s governor, two weeks before his 1971 inauguration, George Wallace married another Alabamian, Cornelia Ellis Snively, 20 years his junior, divorced mother of two and niece of previous Alabama governor Big Jim Folsom. The eventual husband and wife first laid eyes on each other when a past-bedtime, nightgowned Cornelia, age seven or eight (depending on the source), was spotted spying on her uncle’s party in progress from the grand staircase of the Governor’s Mansion by the Wallaces. In Cornelia’s telling, Lurleen declared Cornelia a “mighty pretty little girl.” “And I’ll bet you’ll be even prettier when you grow up,” George added (according to Cornelia).

None described the second Mrs. Wallace as mousy. In Settin’ the Woods on Fire, a PBS documentary on the life and political career of George Wallace, commentator Wayne Greenhaw extolled “knockout” Cornelia’s raven-haired beauty and ability to “fill out a pair of blue jeans.” Cornelia’s mother, Big Ruby, never one to hold back with the press, expanded on her daughter’s physical attributes: “All us Folsoms got big tits.” The Folsoms, men and women, were a tall bunch; George Wallace leveled off at an unimpressive five feet, seven inches. “Not even titty high,” Big Ruby dismissed.

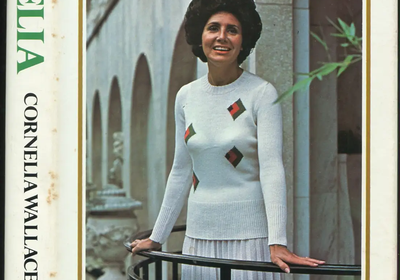

Lurleen Wallace had been a retiring, biddable spouse, a woman never entirely comfortable in the spotlight. With his marriage to Cornelia, Lurleen’s widower joined forces with a different sort of partner. Neither retiring nor biddable (guided, perhaps, by maternal example), the second Mrs. Wallace had lived in and loved the spotlight since her childhood residence in the Governor’s Mansion when Big Ruby had served as her widowed brother’s official hostess. By dent of family ties and legacy, Cornelia had occupied the Governor’s Mansion when George was a mere governor wannabe—not a fact Cornelia was inclined to ignore or downplay in life or in her memoir. “I came from a political family a mile long,” she informs us, the uninformed, in C’nelia. First Lady Frances Folsom Cleveland, wife of U.S. President Grover Cleveland, was a distant relative. When “Uncle Jimmy made his first bid for the United States Congress, Mother campaigned for him the entire nine months she carried me . . . I absorbed my political instincts while in my mother’s womb,” Cornelia writes. Politics, “the king of sports,” is her raison d’être: “I was born in it, I lived in it all my life and I’ve loved every minute of it.”

In 1973, on assignment for Newsweek, Shana Alexander journeyed to Alabama to jointly interview the Wallaces. By the end of that chat, Alexander had concluded that Cornelia Ellis Snively Wallace was “the best thing that could possibly have happened” to politico George.

Judging by her memoir, Cornelia heartily agreed.

The title of her book is the spelling of her name as it is “correctly” pronounced “in the South,” the “r silent,” Cornelia explains. It is also a signal that George Wallace, while present and accounted for, will grace the pages in relation to her, which is not to say the author is unaware her story is being read in no small part because of her connection to him. Shrewdly, she begins with the day of the shooting, the most known and public “event” of the Wallaces’ lives together: “May 15, 1972: To say that it began like any Monday morning at the Mansion would not be true.” Her husband, sights now set on the U.S. presidency, was “unusually irritable, agitated and fidgety.” He wanted to cancel, doubting that “one more day of campaigning could change the outcome of the primary elections” in either Michigan or Maryland. But there was always the chance that the newspaper and television coverage of those last-ditch efforts would keep Wallace’s name at the forefront of “voters’ minds” as they set off for the polling booths. And so the Wallaces set off for another day of campaigning.

One of the ways C’nelia aims to convince readers it possesses the virtue of accuracy is to provide an abundance of detail with regard to George Wallace’s medical condition, surgeries, care and feeding from the moment Arthur Bremer pumped multiple bullets into the presidential candidate as he glad-handed supporters in the parking lot of a Laurel, Maryland shopping center . . .

(George) had a superficial wound on his right forearm and a superficial wound on his right upper arm . . . There was a flesh wound at shoulder level in front and a deep grazing wound above his right shoulder blade. One bullet had entered his stomach, traveled around and lodged in the left flank. Another entered between his sixth and seventh ribs and lodged in the spinal canal.

Reporting on the first paralysis tests, Cornelia quotes verbatim from the “medical charts” (”On the basis of slight denervation activity of diffuse distribution and encompassing the myotomes . . .”) for two full pages. When infection sets in, Cornelia shares the details of “a bulge as large as a grapefruit” on her husband’s side, which, lanced by the surgeon, “gushed . . . enough pus to fill a fruit jar.”

In the aftermath of the shooting, Cornelia vows that George will “never see her cry,” goes without food or sleep for the “first three crucial days,” disdaining the help of “coffee,” “tranquilizers” or “artificial props,” deals with family, doctors, press and visitors (approving of Ethel Kennedy’s athletic good looks, dissing Richard Nixon’s “television makeup” atop “grayish” skin). When a secret service agent, prompted by Cornelia, shares what he has written about her in his report (”either the bravest woman you’ve ever met or a fool”), Cornelia assures the agent and her readers: “The lady is not a fool.” Who is Cornelia Wallace? C’nelia’s cause and function is to convince us she is a glamorous, courageous, devoted, savvy, multi-talented, God-fearing, tough love-administering woman, standing by her man.

Aslim book, C’nelia is plumped by photos of the Alabama Governor’s Mansion “bought by my Uncle Jimmy.” The Folsom clan entire. Cornelia, age four, in a “gypsy” Halloween costume. Cornelia, the striking debutante, in evening dress. A beguiling photo captioned “Me and my friend Martha Mitchell” that, disappointingly, has no textual counterpart of Cornelia and Martha swapping political gossip and advice. Many are the campaign photos: her uncle on the stump, her husband on the stump, Cornelia smiling and standing beside a standing George in the early going and smiling and standing beside George in a wheelchair after his paralysis. As readers will expect, there is a reproduction of the photograph first published in the May 26, 1972 edition of Life of a struck-down Wallace, Cornelia shielding his body from further attack with her own. Amid narrative particulars about the assassination attempt, Cornelia discusses hairdos. On that fateful day, a local hairdresser had styled Cornelia’s hair: “I doubt that Ed could have done any better even if he had known . . . that hairdo would appear on the cover of Life magazine,” Cornelia breezily surmises. Done with chronicling the challenges imposed by the assassination attempt on man and marriage—and how she rose to meet each and every one of those challenges in response—Cornelia turns to happier times: her idyllic existence as a coddled child within the Folsom family nest.

Born in Elba, some 80 miles south of Montgomery, Cornelia flourished in a small town setting and recommends the same environment for all youngsters. (”Growing up in a small town is an experience every American child should have.”) Her father, Charles Ellis, a civil engineer, did not, as time revealed, live up to Big Ruby’s manliness bar. Whereas her mother was “gregarious, assertive and ambitious,” her father was “conscientious, serious and inhibited,” Cornelia writes. “No matter how hard he tried, Daddy could not outmeasure the Folsoms. Neither could any of his achievements match those of Jim Folsom, who was the yardstick by which my mother measured all men”—a yardstick her daughter clearly shares.

C’nelia tracks no downside to the parental divorce, only advantages. Raised thereafter with her brother in the Governor’s Mansion alongside widower Big Jim’s two youngest daughters, Cornelia assumed leadership of the children brigade, pampered and praised for her looks, talents and social grace. By age eight, she possessed her own stack of “calling cards.” Young Cornelia played piano and saxophone, danced (”tap, ballet and toe”), performed as a majorette and recited poems “at assembly.” In high school, she wrote for the school newspaper, sang in the choir and served as church organist on Sunday nights, already a staunch, baptized Christian. All the stars aligned until they didn’t. Flabbergasted by her early elimination in the Miss Alabama beauty contest, she swore “never again to enter the Miss Alabama contest.” Other disappointments loomed. As a University of Alabama freshman in Fall 1957, she was “shocked and terribly crushed” to be “noticeably left out” when sorority rush “invitations were issued.” The reason, according to Cornelia: her uncle’s “liberal” politics. “People said Jim Folsom was too soft on the question of integration.” Insulted because no one at the time “bothered to ask” whether she “shared” her uncle’s opinion, in her memoir Cornelia clarifies: she was and is staunchly anti-integration. “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” would not be an issue that divided Cornelia and her future husband.

Snubbed by UA sororities, in a fit of pique, Cornelia transferred to Huntington College in Montgomery. Passing on campus accommodations, she boarded with mom. Living with mom, if mom was Big Ruby, put no damper on a daughter’s ambitions and plans. Big Ruby pulled some strings, got Cornelia a screen test with MGM Studios in New York and drove her daughter to the big city during Christmas break. (”I wanted her to be a movie star all her life,” Big Ruby later told the press.) Cornelia preferred to audition for MGM’s record label. Since Cornelia’s is a memoir more about politics than music, her MGM recording contract, songwriting (e.g., “Baby with the Barefoot Feet”), romance with Phil Everly, and touring years with Roy Acuff are logged rather than explored. A job as the featured water-skier at Cypress Garden in Florida brought with it “a new outlook on life. It was like getting paid while you were on a summer vacation.” And then, with only locale serving as transitional link, a one-paragraph summary of marrying for the first time and becoming a mother: “While I was skiing at Cypress Gardens I met and married John Snively III” (described elsewhere as a “wealthy citrus grower”). “I had two sons, Jim and Josh Snively, before my marriage ended tragically in divorce seven years later, in 1969.”

The stage was set for a return to Montgomery and a reconnect with Uncle Jim’s one-time protégé George Wallace. Cornelia decided to attend a Wallace rally with her sons, she explains, because she “wanted them to appreciate their political heritage.” (Appreciate their heritage or glimpse their future? the reader may reasonably wonder.) “Now that (Wallace) was virtually the most eligible man in town, I began to think of him in a different way,” Cornelia writes. The courtship remained discreet, given Lurleen’s recent passing. When Cornelia realized she’d “fallen in love with George,” she “tried to analyze” her attraction. The reason she came up with: “In essence, he was every man I had ever loved all in one.”

As presented by Cornelia, the every-man-in-one she loved was hard of hearing, requiring her “to pitch and project (her) voice in such a way” that her “words never fell on deaf ears.” His favorite condiment was ketchup, which he poured liberally on most food placed before him. His favorite TV show was Hee Haw. “Like all good politicians, he was very conscious of ‘bad breath.’” He “loved to read his mail.” He “got very annoyed if members of the road crew laughed or talked loudly while his speech was in progress.” As a politician, he was “cagey, crafty . . . the hero of countless political battles,” beloved for his “gutsy, aggressive style.” As husband and wife, “every morning” the Wallaces “enjoyed the intimacy of sharing the bath.” Wallace liked to receive foot massages that Cornelia liked to administer. (”It was a private thing we shared and one from which he derived much pleasure.”)

The twosome married with their “children’s blessings” in 1971. They were still “enjoying the blissful ecstasy of an extended honeymoon” when Wallace “embarked on the whirlwind presidential campaign of 1972,” Cornelia writes, assigning a number to those days of bliss: “I was a bride of only one year and four months when my husband was suddenly gunned down in Laurel, Maryland on May 15, 1972.”

In its final chapter, C’nelia returns to its author’s uphill battle to “pump up” her depressed, disabled husband who wants only to stay in bed, indulge in crying jags, and call her “mama.” (Cornelia nips that “mama” business in the bud.) She refuses to countenance the “self-pity” George is “drowning” in, reminds him that he has “had to struggle all his life” and will “triumph over this tragedy as he had the others.” When that battery of encouragement fails, she plays the God card, as in: what happened happened because it was “part of God’s plan.”

At last comes the day when Wallace acknowledges Cornelia’s predominant role in his two-year “complete recovery.” In that “precious” moment, Cornelia writes, George “poured out his heart to me . . . told me how very much he loved me . . . that he couldn’t have made it without me . . . how much he appreciated all I had done for him.” In response, Cornelia “felt a deep and total contentment that only comes with the security of true love.”

It was a security short lived. A year after Cornelia’s memoir was published, the fractured state of the George/Cornelia union became widely known when the Washington Post reported that a “small blue van” had pulled up to the Governor’s Mansion on September 6, 1977 and “moved out” Cornelia and her belongings. Away from the public eye, the marriage was in crisis . . . In Wallace, Marshall Frady furnishes a taste of the operatic drama and acrimony of the final split. Cronies whispered in George’s ear about Cornelia’s liaisons; she, in turn, tapped George’s phone, convinced he was indulging in phone sex with “prior consorts.” Initially, when trouble came calling, Cornelia dug in her heels, refusing to divorce. “George wanted the divorce. I didn’t,” she later told People magazine. “There were other people influencing him . . . People who wanted to be close to George’s power fought to get me out of the picture.” Each party sued the other. Ultimately, in an out-of-court settlement, Cornelia received $75,000 and a portion of the community property. But Cornelia wasn’t done. Even after the divorce papers were signed, Frady reports, the former first lady would occasionally “storm” the mansion, only to be “forcibly ejected.” She also stayed on in Montgomery. As had predecessor Lurleen, Cornelia ran for governor, joining a field of twelve other candidates in the 1978 race, one of those aspirants her Uncle Jimmy, 69 years old, “legally blind and partially deaf” (Washington Post). Unlike Lurleen, Cornelia did not triumph. In a statement to the press, she blamed her failure on the sitting governor, who had refused to endorse the candidacy of wife number two. When rumors began to swirl that George planned to marry again, a woman thirty years younger this time around, Cornelia “issued a public call for prayer by Alabama’s citizens to avert that gruesome prospect.” It was evident to any and all, Frady reports, that Cornelia was “wheeling into a full Folsom-scale breakdown.” In 1985, her mother and brother had her committed to Searcy Hospital, a state-owned and -operated facility in Mount Vernon, Alabama. Upon release, she once again moved in with Big Ruby . . .

George Wallace died in 1998. As for Cornelia, cancer “killed her dead,” as they say in the South, at the age of 69 in 2009. In one of her last interviews, she announced that she was working on a second book, a “political,” “historical” novel, working title The Giant Slayer. The main character, she said, closely resembled her Uncle Jimmy. A second, less heroic character was based on ex-husband George, “who needs to slay the giant in order to feel big.” There was also a character based on herself, a woman who “functioned very well at a high-paced fever pitch”; a woman who, when she “wanted something, kept going until she wore everybody down.”

In C’nelia, tucked among reminiscences of her sublime childhood, Cornelia describes a happenstance sighting of Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, strolling along a fashionable Montgomery street, alone. As a third-grader, Cornelia didn’t realize her “eyes had fallen on a tragic romantic heroine,” the “wife of a literary genius.” As an adult memoirist, Cornelia doesn’t seem to grasp she is describing her situational kin: another ambitious, frustrated, Alabamian woman unsatisfactorily married to a man more famous than herself.

Kat Meads's essays have appeared in Full Stop, New England Review, AGNI online and elsewhere. Her most recent book is These Particular Women (Sagging Meniscus, 2023).