-

-

The Discerning Mollusk's Guide to Arts & Ideas

-

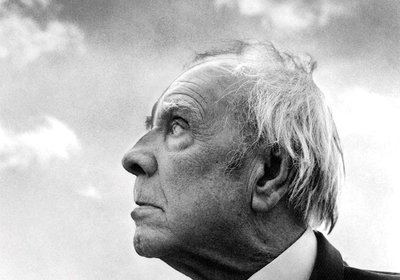

orge Luis Borges needs no introduction, I think to myself. Then I think again, recalling that we are living through a new dark age when much of the past, including the literary past, is being discarded wholesale in a kind of cultural amnesia or cultural lobotomy. And I think perhaps I had better introduce him anyway.

He was born in 1899 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and died in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1986 at the age of 86. Among other things we can say about the young Borges, he would have instantly recognized the reference to a line by Browning in the title of this essay. He was raised to be bilingual, speaking only English until age four. His knowledge of English and American literature was encyclopedic, surpassing any other Latin American writer of his generation. No doubt this was instrumental in his eventual choice of profession: librarian. Has anyone ever written so often or so imaginatively of libraries and librarians?

Borges started writing as a child and never stopped, perhaps influenced by his father, Jorge Guillermo Borges Haslam, a successful lawyer and teacher, but a failed writer. As the son would later experience, the father also had deteriorating eyesight, and moved the family to Geneva, Switzerland, in 1914 so he could receive medical treatment. They remained abroad until 1921, after spending a few years in Spain. It was there that Borges affiliated briefly with the avant-garde Ultraist movement, which was a reaction against Modernismo.

Back in Buenos Aires, he wrote furiously, publishing his first book of poetry in 1923, Fervor de Buenos Aires (Fervor of Buenos Aires), and his second in 1925, Luna de enfrente (usually translated as Moon Across the Way, though in person I heard him call it The Moon Across the Street). In 1925 there also came his first book of essays, Inquisiciones, (Inquiries). He made important longtime friends, such as Victoria Ocampo, founder of Sur magazine, the country’s leading literary organ, and Adolfo Bioy Casares, who would become his close collaborator. Although poetry was his first love, and he never gave it up, he devoted more time to the short prose hybrid forms on which much of his fame is justly based. Borges is almost certainly the most influential fiction writer who never completed a novel. He inspired not only generations of writers in his own language, but also in English and many others.

The other significant thing that happened during those early years was the gradual onset of his blindness. In 1928 he had the first of eight eye operations. Within 25 years he was completely blind. This tragedy affected every aspect of his existence. Yet he managed to find some blessings in it. One of his later books of poetry is called Elogio de la sombra (1969) (In Praise of Darkness). Of necessity, blindness sharpened his hearing and his memory, two gifts that made him a better poet.

Before I embark on an analysis of his tiny poem “A Minor Poet,” I need to recount two of my own memories. The first is of a visit Borges made to Northwestern University in Chicago. I think it was 1974. He had been famous in America for two decades by that time. The place was packed. Borges spoke for a bit about his love for English and American literature, and how that love influenced his own work. He recited some favorite poems from memory, along with a few of his own. Then he took questions.

Someone who knew his work well asked what a particular line in one of the poems from his second book was about. I wish I could remember which line and which poem! Anyway, that’s when he referred to the book as The Moon Across the Street. He was somewhat dismissive of his early work. “Honestly, I don’t know what I meant,” he admitted. “Probably I was just trying to come up with the most startling image possible. That’s what I did in those days.”

Another person asked who were his favorite American poets. Not surprisingly, he mentioned Whitman and Dickens and Frost. But there was an audible gasp of surprise and embarrassment when he said he loved Carl Sandburg, then very much out of favor with the literati. Maybe he still is, I don’t know. Borges quoted “Fog,” the one we were all taught as schoolchildren, and I believe he mentioned “Chicago” and “Washington Monument by Night,” two more great American poems, no matter what trivial fads and shunnings may occur in our little literary pond. Sandburg’s love for his native city must have resonated with the man who had a lifelong love affair with his own Buenos Aires.

I asked a question as well, which is the subject of one of my two tribute poems accompanying this essay, the one called “What Borges Said” (the other is called “Another Minor Poet”). It was an idiotic question—what did he think of the horror and science fiction author H. P. Lovecraft? Still, he answered it in a way that made me feel slightly less idiotic while casually revealing the depth of his knowledge. How many American poets alive then could have done that? Precious few.

My question was perhaps the second stupidest one that day. I am pleased to report that the most imbecilic question was asked by another preening windbag. This nitwit wanted to know if Borges would comment on Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow and what he called “the gravity of comedy.” That sprawling novel had just been published the year before. Today many critics regard it as one of the finest American novels. That’s as may be. Yet how fatuous to assume that Borges would have had any chance to read it. I doubt very much whether there was an audio or Braille version at that time. The only way Borges could have known the book is if he had had someone read it aloud to him, all 760 densely-packed, surreal and paranoid pages.

After the event, I had a chance to say hello and thank you to Borges. Just that, not even my name. But that was enough.

Fast-forward 38 years to 2012. Life, divorce and the vagaries of my so-called career had exiled me to Lewiston, Idaho, away from my children and any trace of human civilization. It was the worst two years of my life. Except, there was a good university nearby in Moscow, Idaho, and also a top-notch independent bookstore, BookPeople. One night they had a special event featuring Willis Barnstone, an excellent poet and easily one of the two or three best translators in the English language. Right now I’m looking at a copy of his first published work, 80 Poems of Antonio Machado, from 1959. Good luck finding that anywhere at any price, though I will gladly let you come to my house and read it while I sit nearby with a loaded revolver.

I said hello to Barnstone and thanked him for his many translations, singling out those he had done of Borges. That got him reminiscing and talking. We spent the next hour on a couch discussing Borges in general and that visit to Northwestern University in particular. It turned out Barnstone had been one of his assistants and handlers on that lecture tour. I had already met him, in fact, all those years ago. He was 47 on that day in 1974 and 85 as we sat in BookPeople chatting about it, and it was as if not a moment had passed. He remembered every detail of the talk by Borges and also the questions, including mine and the one from the fan of Gravity’s Rainbow.

Meanwhile, I was shamelessly monopolizing him, and the other attendees were getting increasingly annoyed and restless. I reluctantly released Barnstone back into the wild, deeply moved by this unexpected encounter. Something had been reawakened in me: the love of poetry. Not just reading it, but trying to write it again. A couple of years later I abandoned humor writing after several decades with the Onion and stints writing for television and radio. I returned to my first love, poetry. And in part I have to thank Jorge Luis Borges and Willis Barnstone for realigning my chakras, or whatever that was on those two mysteriously connected occasions.

As you can see, this essay is very personal for me. They say you should never meet your heroes. However, I met one of mine in 1974—two, actually—and they did not disappoint.

The Borges poem we’ll be looking at here is one of his shortest, only two lines and eight words (nine in the original Spanish), or 11 words counting the title, “A Minor Poet.” It should not be confused with an earlier poem bearing a similar title and theme, “To a Minor Poet of the Greek Anthology,” which has been beautifully rendered in English by W. S. Merwin. This later, much more concise poem was first included in the book The Gold of the Tigers: Selected Later Poems (1977), translated by Alastair Reid. Technically, it is part of a set of otherwise unrelated brief poems gathered under the title “Fifteen Coins.” I believe this means we are allowed to quote it in full here, as it was originally part of another longer poem.

Regardless of how it was first presented to the world, it stands on its own:

A Minor Poet

The goal is oblivion.

I have arrived early.

In case you were wondering, it is just as simple and unadorned in the original Spanish as it is in English. It does not rhyme. It is too short to establish any other distinctive sound patterns involving alliteration or assonance. Nor does it feature any “startling images” like those that festooned his earliest poems, the ones I heard him speak of almost with contempt or regret. It was said that later he bought up any copies he could find of some of them, simply so that he could destroy them and return them to oblivion.

No, this little poem depends almost entirely upon the most direct, straightforward kind of statement. Yet so much is contained in it, I feel. The key word, I believe, is “goal.” “The goal is oblivion.” Not, “The result is oblivion,” or “The thing that happens is oblivion,” or “The destination is oblivion.” The goal. Whose goal, though? Surely not the poet’s. God’s goal, maybe? The goal of the universe, or existence? How strange, if the goal of existence is nonexistence, as if existence is some sort of aberration. And why oblivion instead of, say, death or darkness or silence? Oblivion, total erasure, seems more final than any of those I suppose. These unspoken and unanswered questions linger in the mind long after reading the poem.

The second and last line—what would be the punchline if this were a joke (and perhaps it is in a way)—is a real heartbreaker: “I have arrived early.” Of course, part of being a minor poet, the fate of nearly all of us, is that we never arrived anywhere at all. We tried, we gave it our best shot, we may even have written a few lines or a few poems worth remembering. Only they will not be remembered. Nor will we. Oh, oblivion, yes, there’s a goal we all can meet! Some sooner than others, that’s all.

We can think of this poem almost as one of those tantalizing fragments by Sappho (Willis Barnstone translated her too, check it out), pieces of lost poems so intense that even in partial form they remain poems in their own right. It’s nearly a fractal of the earlier, longer poem (which is also a great poem), and yet it contains all that matters from that poem. It has not quite reached the goal of oblivion, though it is getting awfully close. Ironically, by writing it along with so many other memorable verses, Borges will not be arriving early at oblivion. Make no mistake, however, he will arrive at the place that receives us all, minor poets and major alike. And there may be worse things than oblivion. You could be the poor hapless fool who asked that silly question about Gravity’s Rainbow. To quote yet another minor poet, “So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.”

After years of writing humor for the New Yorker, the Onion and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, among others, Kurt Luchs returned to his first love, poetry, like a wounded animal crawling into its burrow to die. In 2017 Sagging Meniscus Press published his humor collection, It’s Funny Until Someone Loses an Eye (Then It’s Really Funny), which has since become an international non-bestseller. In 2019 his poetry chapbook One of These Things Is Not Like the Other was published by Finishing Line Press, and he won the Atlanta Review International Poetry Contest, proving that dreams can still come true and clerical errors can still happen. His first full-length poetry collection, Falling in the Direction of Up, is out from Sagging Meniscus as of May 2021.